Variables We Cannot Control: Notes on Growth, Failure, and Mrs. Anderson's Calculator Incident

My calculator broke during a seventh-grade math test.1 The screen flickered, numbers vanished, and I sat frozen, unable to compute basic multiplication—a state of technological abandonment which, in retrospect, seems almost cosmically orchestrated in its timing and resonance. Mrs. Anderson noticed my panic and walked over. Instead of lending me her calculator, she pulled up a chair.

"Work it out on paper," she whispered. "Sometimes the long way teaches us more." The kind of statement which, when uttered by a middle-school math teacher2, carries both the weight of pedagogical authority and a particular brand of optimistic sadism unique to educators who believe in "learning opportunities."

I spent the next hour breaking down complex equations into smaller pieces, documenting each step with the kind of obsessive detail usually reserved for conspiracy theorists mapping connections on their bedroom walls. When other students finished early and left, I remained, wrestling with numbers in what felt less like mathematics and more like a prolonged negotiation with abstract concepts that had suddenly developed personalities and grievances.3

Twenty years later, this memory surfaces whenever I encounter obstacles in personal development—which is to say, approximately every seventeen minutes of conscious existence. We search for shortcuts—books, podcasts, seminars—hoping to download wisdom directly into our brains, as if personal growth operated on the same principles as software updates.4 These resources offer value, but they often bypass an essential truth: meaningful growth demands active engagement with challenges, a truth so obvious it becomes invisible, like air or the endless stream of pharmaceutical commercials during evening television.

Consider the aspiring public speaker who studies presentation techniques but never steps onto a stage. Or the writer who reads about writing but never faces the blank page.5 Knowledge without application becomes mere intellectual decoration, a mental shelf of participation trophies for races never run. We accumulate theories and frameworks the way bower birds collect shiny objects—with great enthusiasm but questionable utility.

The brain operates as both ally and saboteur in this process, a dual role it performs with the same level of commitment your friend shows when claiming they'll "definitely" attend your experimental poetry reading.6 Our neural circuitry—evolved over millions of years to keep us alive in environments where every rustle could signal death—now applies the same threat-detection algorithms to social situations and personal challenges with all the nuance of a sledgehammer performing microsurgery. When we attempt something new, these ancient warning systems flood us with alerts: What if you fail? What if people judge you? Better stick with the familiar. The modern brain interprets social rejection with the same urgency our ancestors reserved for approaching predators, which explains both anxiety disorders and the enduring popularity of social media validation.7

A counterintuitive solution emerges from an unlikely source: scuba diving—though before you abandon this essay in anticipation of yet another tortured metaphor comparing personal growth to underwater activities8, consider the principle of neutral buoyancy. Underwater, divers maintain a state where they neither sink nor float, requiring constant micro-adjustments based on environmental feedback. Personal growth follows similar principles, minus the expensive equipment and persistent fear of decompression sickness. We must calibrate our actions based on real-world feedback, making continuous adjustments as we progress through the murky waters of self-improvement.

Small choices accumulate into transformative changes with the steady persistence of geological processes, though significantly faster and with less impressive mineral formations.9 Each decision—to show up, to try again, to stay consistent—builds momentum in ways both observable and imperceptible. A fifteen-minute workout might seem insignificant, but it reinforces an identity beyond physical fitness. It declares: "I keep promises to myself," a statement which, in the grand accounting of personal development, carries more weight than all the motivational posters ever printed.10 These micro-commitments construct the foundation of lasting change, brick by unremarkable brick, in a process so gradual it often escapes notice until we suddenly realize we've become someone who actually enjoys eating vegetables or reading financial statements.

Growth rarely announces itself with fanfare—a fact which seems, in the age of social media milestone announcements and LinkedIn humble-brags, almost rebelliously understated.11 Often, we only recognize change in retrospect, looking back at the person we were and barely recognizing them, like finding an old photograph where you're wearing clothes you swore you never owned. The storm metaphor falls short here—storms pass quickly, while transformation occurs gradually, imperceptibly, through sustained effort and attention. We become different people through such small increments we barely notice the transition, until one day we realize we've crossed an invisible threshold into a new version of ourselves, a process which raises uncomfortable questions about personal identity and consciousness that philosophers have been arguing about for millennia without reaching any particularly satisfying conclusions.12

What obsesses you? Which activities pull you in so completely you lose track of time? These questions reveal potential paths for growth, assuming your obsessions don't involve anything illegal or excessively weird.13 When we align our development with genuine interests, resistance diminishes—though it never disappears entirely, because the universe maintains a strict policy against making anything too easy. The mathematician solving equations for pleasure, the painter losing hours to their canvas—they've found their resonant frequency, a state of engagement where difficulty transforms from obstacle to invitation, like a challenging puzzle that frustrates and delights in equal measure.

Success leaves clues, but they often hide in unexpected places, requiring a kind of intellectual scavenger hunt through seemingly unrelated disciplines.14 The tree's growth rings tell stories of drought and abundance, adaptation and resilience—patterns which repeat across scales and contexts with the kind of elegant consistency that makes complexity theorists weak in the knees. Public speaking contains similar patterns: rhythm, timing, response to environment. By drawing connections between disparate fields, we expand our understanding and discover new approaches to old challenges, a process which occasionally produces insights so obvious in retrospect they make you want to travel back in time and slap your younger self.

Remember my calculator's demise? The long way proved more valuable than the shortcut, a lesson the universe seems determined to teach repeatedly through increasingly elaborate scenarios.15 Real understanding emerges from engagement with difficulty, from pushing through resistance when easier options beckon. Each evasion, each procrastination, each word and action—they all count toward who we become, accumulating with the precision of compound interest and the inevitability of death and taxes (though with generally more positive outcomes).

Your growth belongs to you, a statement which sounds simultaneously obvious and profound, much like most fundamental truths about human existence.16 No expert can hand you a formula for personal development, despite the endless parade of books and seminars promising exactly that. They might offer frameworks, suggestions, or encouragement, but the real work happens in the space between knowledge and action, where you decide to move forward despite uncertainty. This space—this gap between knowing and doing—contains all the potential energy of transformation, like a quantum field of possibility waiting to collapse into reality through the act of trying.17

Years after my calculator died, I found it in a box of middle school memorabilia. The screen remained dark, buttons unresponsive—a small electronic corpse preserved in plastic. I almost threw it away, but something stopped me. The device sat on my desk for weeks, a monument to technological failure turned accidental wisdom.18

Here's a mathematical truth about growth: Every solution contains variables we can't control, constants we must accept, and operations we'd rather avoid. The elegant answer—the shortcut, the life hack, the ten-step formula—tempts us with its simplicity. But real transformation demands we sit with the problem, show our work, accept the mess of learning.

Mrs. Anderson knew this. The trees know it, recording their struggles in concentric rings. The scuba diver knows it, adjusting breath by breath in the deep. And somewhere inside ourselves, beneath layers of resistance and rationalization, we know it too.

The calculator still sits on my desk. Its blank screen reflects my face, older now but still searching for answers. Sometimes I pick it up, press the power button, and watch nothing happen. Then I reach for a pencil, and in the act of writing down the problem—any problem—I remember: The long way isn't just a path to the answer. The long way is the answer.

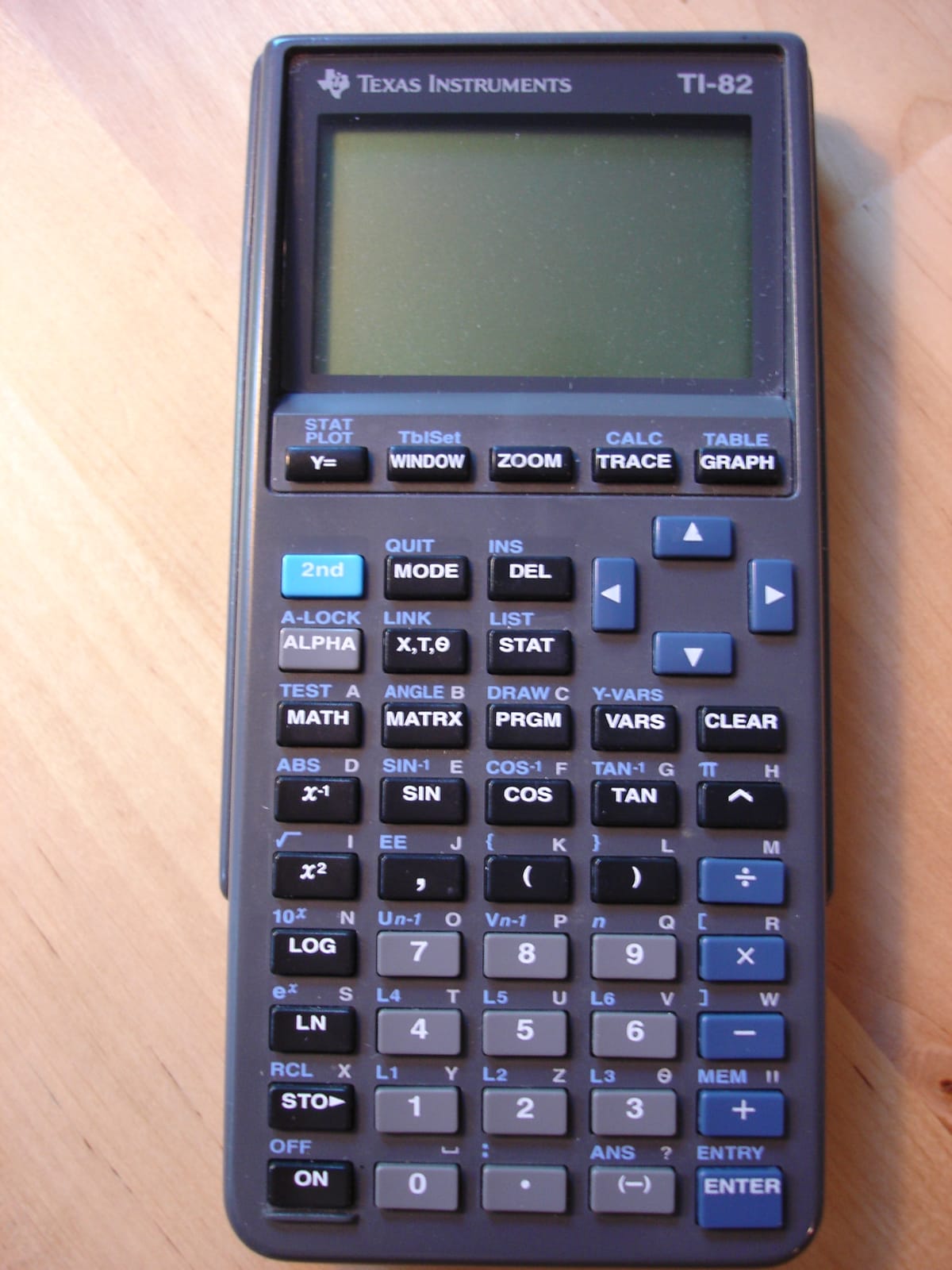

1. The calculator was a TI-83 Plus, a device whose computational power exceeded everything NASA used to reach the moon, yet proved insufficient for a 10-year-old's basic arithmetic needs—a commentary on both technological dependence and human capability I'll leave for another time, or possibly never address, much like my unfinished eighth-grade science project.↩

2. Mrs. Anderson wore cardigans in every color of the pastel spectrum and collected ceramic owls, details which seemed irrelevant then but now strike me as essential components of her character and teaching philosophy.↩

3. The anthropomorphization of mathematical concepts remains a surprisingly effective coping mechanism for academic stress, though explaining this to your therapist requires careful phrasing.↩

4. If personal growth actually operated like software updates, we'd all have a convenient "Remind Me Tomorrow" button for difficult emotions and challenging situations, which sounds both appealing and dystopian.↩

5. The accumulation of theoretical knowledge without practical application creates a peculiar form of cognitive dissonance, where we simultaneously know everything about a subject and nothing at all—Schrödinger's expertise, if you will, though this physics reference probably deserves its own footnote explaining why science metaphors in self-help contexts often create more confusion than clarity.↩

6. A commitment level roughly equivalent to "I'll definitely start eating healthier after the holidays" or "I'll just check social media for five minutes."↩

7. The amygdala, our brain's threat-detection center, can't distinguish between a lion and a LinkedIn rejection—an evolutionary oversight that explains both social anxiety and the entire self-help industry.↩

8. The metaphor-to-insight ratio in personal development literature often approaches dangerous levels, threatening to collapse into pure abstraction, yet here we are, adding another one to the pile.↩

9. Though if personal growth did produce mineral formations, they'd probably make excellent conversation pieces for dinner parties.↩

10. The motivational poster industry, a subset of corporate decor that somehow survives despite universal agreement about its aesthetic and philosophical bankruptcy, deserves its own anthropological study.↩

11. Social media has created a peculiar expectation that all personal growth must be documented, hashtagged, and shared with appropriate filter treatments, #blessed #personaldevelopment #authenticity.↩

12. The Ship of Theseus paradox applied to consciousness raises questions about personal identity that philosophy professors have been using to torment undergraduate students for generations.↩

13. The definition of "excessively weird" remains subjective and culturally dependent, though collecting belly button lint probably qualifies regardless of context.↩

14. Cross-pollination between disciplines offers fresh perspectives, though sometimes produces connections so tenuous they'd make a conspiracy theorist blush.↩

15. The universe's dedication to teaching through increasingly elaborate object lessons suggests either a cosmic sense of humor or a fundamental lack of faith in human learning capabilities.↩

16. The paradox of profound obviousness appears throughout philosophy, psychology, and fortune cookie messages with remarkable consistency.↩

17. The quantum mechanics metaphor probably makes actual physicists cringe, but it captures something true about potential and actualization that more accurate scientific comparisons would miss.↩

18. The human capacity for self-deception roughly equals our capacity for pattern recognition, creating an ongoing internal debate between growth and comfort, usually mediated by snack foods and Netflix autoplay.↩