Victoria’s Secret: How One Woman Tried to Break America’s Mold

It's a cold January Inauguration Day afternoon, the kind of cold that seems scientifically calibrated to remind you that winter is less a season and more an annual endurance test, and another President—hand raised, face locked in a grimace of performative gravitas—swears to defend ideals that everyone sort of agrees mostly exist in history books or maybe campaign speeches (which are kind of like history books but with less editing and more people clapping). It’s worth recalling an audacious moment in American history—one so outrageous to its contemporaries it was dismissed as a farce, a fever dream, a thing best extinguished by laughter.

So: 1872. Victoria Woodhull, a woman who—depending on who you asked—was either a visionary genius or a walking scandal with a gift for public humiliation, ran for President of the United States.1 This was not, repeat, not some kind of publicity stunt or a late-19th-century ‘punking’ attempt (to the extent that such a thing even existed back then); this was a real candidacy, with an actual platform—a platform that makes our contemporary ‘let’s pretend to care about change’ platforms look about as revolutionary as a new app that lets you send pictures of your breakfast to strangers. Her running mate? Frederick Douglass. Yes, that Frederick Douglass—abolitionist, orator, former slave, American icon.2 The pairing feels like a piece of speculative fiction someone forgot to label as such.

Predictably, the press lost its collective mind. The campaign was called ‘a brazen imposture’—a phrase that manages to sound both archaic and vaguely British, like something your uncle who collects stamps might mutter under his breath. The moral superiority behind such statements—then and now—has the same quaintness of a chamber pot: technically functional, deeply unpleasant, and astonishingly consistent with the time’s obsession with ensuring that women stayed firmly in their metaphorical and literal places.3 The sheer existence of her candidacy was treated not as a challenge to the political status quo but as a kind of cosmic joke, an affront to the natural order. But you know what? Despite—or maybe because of—the vitriol, people showed up. Not just people, but marginalized people, people whom society had spent centuries teaching to expect nothing—the factory workers, the freed slaves, the disenfranchised women—showed up to hear her speak. And they didn’t just listen.

They cheered, loudly and relentlessly, as if the very act of being there was a declaration of war on the forces keeping them invisible. Their cheers weren’t just noise—though they were that too, gloriously so, the kind of noise that makes dogs bark and uptight neighbors write passive-aggressive notes—but also a kind of temporary architecture, scaffolding for a momentary rebellion, each shout a hammer blow rattling the increasingly fragile drywall of the status quo.

To understand Woodhull’s audacity, you first have to understand where she came from. Born in 1838 in Homer, Ohio, she was the seventh of ten children in a family so dysfunctional Dickens would have thrown the idea away as too crazy. Her father, Reuben Buckman Claflin, was a con artist whose greatest skill was setting things on fire—literally, in the case of his gristmill, which he torched for the insurance money. Her mother, Roxanna Hummel Claflin, was an illiterate religious zealot who alternated between claiming to commune with the divine and physically abusing her children.4 By 14, Woodhull had escaped her father’s tyranny only to land in a marriage that was, if anything, worse: a much older doctor who had two qualities: alcoholism and staying alive long enough to make her life miserable. “I now know that I had gone to hell,” she later wrote, summing up her first marriage with devastating precision.5

And yet, Woodhull didn’t vanish into the anonymity reserved for people born into such relentless misery. Instead, she transformed herself into something unrecognizable. She became a spiritual healer—not the crystal-waving caricature that term conjures today, but a person whose understanding of the human condition seemed to border on preternatural, who traveled the country offering a kind of metaphysical solace to people who, like her, were drowning in a world that didn’t particularly care if they lived or died.6 It was through this work that she developed an unflinching view of American suffering. She saw enslaved people, factory workers, women whose lives were legally considered property, and she understood—perhaps better than anyone else—that the machinery of oppression wasn’t just brutal; it was efficient. “I come before you,” she once said, “to proclaim the truth as I see it, as I have experienced it, as I have found it in this world.”7

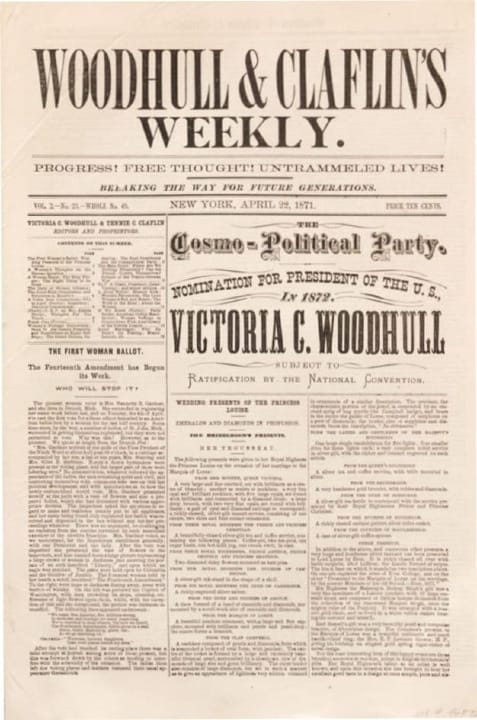

By her early 30s, Woodhull had become a walking scandal. Divorced (unheard of), remarried (still scandalous), and operating the first woman-owned brokerage firm on Wall Street (so outrageous and improbable, you probably want to double-check). She used the profits from that enterprise to fund a newspaper with her sister, Tennessee Claflin, Woodhull & Claflin’s Weekly, which served as a kind of DIY megaphone for her radical ideas—reproductive rights, marital autonomy, sexual freedom, and the notion that women’s bodies weren’t communal property. "I am a free lover," she said—at which point you can practically hear every monocle in Victorian America dropping into its respective teacup. "I have an inalienable, constitutional, and natural right to love whom I may, to love as long or as short a period as I can; to change that love every day if I please."8

And then, because apparently she hadn’t done enough to upset Victorian sensibilities, she announced her candidacy for President. Her platform was revolutionary, even by today’s standards. She called for women’s suffrage, labor reform, and the redistribution of wealth. She argued, without flinching, that forced motherhood was a form of slavery. It was a statement designed to provoke, and provoke it did.

Her campaign wasn’t just ambitious; it was prophecy. Woodhull wrote about the dangers of monopolies, the creeping influence of corporate money in politics, and the ways in which systems ostensibly designed for freedom could be weaponized against it. She warned that wealth, if left unchecked, would become indistinguishable from governance. The fact that she was railing against railroads—actual railroads—rather than Silicon Valley makes this all the more unnerving. It’s not that she was ahead of her time; it’s that time hadn’t caught up yet. “The aristocracy of wealth and the aristocracy of labor will forever be at war,” she wrote, a statement so clairvoyant it’s hard not to feel a little nauseous reading it now.9 Woodhull’s candidacy wasn’t just improbable; it was incendiary. This was a person who didn’t just want to break rules; she wanted to rewrite them in real time.

But for all her vision and brilliance, Woodhull was undone by the same forces she sought to dismantle. In the months leading up to the election, she published an exposé in her newspaper accusing the Reverend Henry Ward Beecher—a popular minister and vocal critic of free love—of having an affair (if this feels oddly familiar—like an early prototype for the sort of character assassination we’ve perfected in the digital age—that’s because it is). The backlash was immediate and ferocious.

Just days before the election—because the universe has a keen sense of irony and an almost psychopathic sense of timing—Woodhull was arrested on obscenity charges. Obscenity, in this case, being defined as: daring to suggest that men who preached morality and purity might, on occasion, be full of shit. The timing of the arrest was so laughably blatant that even calling it ‘retaliation’ feels like an insult to conspiracies everywhere. The press, gleeful as always when provided with a target both unconventional and vulnerable, declared her a fraud, a failure, and—most cuttingly—a joke. "This woman has lost every vestige of decency," one editorial sneered, proving, once again, that moral indignation is often just fear wearing its Sunday best. And just like that, the campaign was over.10 Her arrest wasn’t just a public humiliation; it was a flashing neon warning sign, a loud, unmistakable message for anyone else stupid enough to consider rocking the boat.

She left America soon after, retreating to England where she lived out her days in what could charitably be called obscurity, reinventing herself as a more conventional figure. She lived into her late 80s, long enough to see women finally get the vote in America but not long enough to see the world she’d dreamed of. The systems she railed against—the consolidation of wealth, the commodification of human lives—remained stubbornly intact. The world, it seems, moved on. Railroads became tech platforms, and tycoons became billionaire tech bros. The rhetoric about freedom remained, but it became increasingly difficult to pinpoint what, exactly, was free. The systems she decried were rebranded, polished, and re-released, but they were never dismantled.

What do we do with this? Woodhull’s story is infuriating because it resists the neat resolutions we crave. It’s not a triumph; it’s not a tragedy. It’s more a glitch in the matrix, one that forces you to stare directly into the cracks and question the entire design. We want history to be a straight line, a tidy narrative of progress marching forward. But her story reminds us that progress isn’t linear—it’s more like one of those funhouse mirrors: distorting, fragmented, occasionally cruel, but still somehow a reflection of us, if we squint hard enough.

That we’re still fumbling through this carnival—hesitant, stumbling, occasionally face-planting—doesn’t mean we’re failing. It just means we’re human, which is both the problem and, maybe, the point. Woodhull once wrote, "Progress sometimes forces a temporary halt, that it may summon the strength to advance again."11 But the truth—the one no one wants to say out loud—is progress isn’t inevitable. It’s fragile, flammable, and often indistinguishable from collapse. Her story is a warning wrapped in kindling, demanding we carry the fire forward, even as it scorches our hands, because the alternative—the cold, the dark—is so much worse.

1. The sheer audacity of this is almost overshadowed by the fact that so few people know about it. History, it turns out, isn’t written by the victors but by the people who decide what counts as worth remembering. History isn’t neutral; it’s an act of will.↩

2. Douglass didn’t formally agree to the role or even acknowledge its occurrence, which feels both understandable and like the kind of historical footnote that should come with its own Netflix special. (Imagine the boardroom pitch: “Okay, it’s about a radical suffragist who runs for President with Frederick Douglass on the ticket. The twist? He has no idea.”)↩

3. Victorian journalism was essentially an arms race of hyperbolic shaming. If they’d had access to Twitter, they would’ve melted it. The insults were almost comically overwrought, as if the mere existence of Woodhull’s campaign required an entire moral universe to implode.↩

4. The Claflin family was the kind of nightmare that would make social workers break out in a cold sweat. Imagine a Wes Anderson movie directed by David Lynch, with just enough documentary footage to remind you it’s all horrifyingly real.↩

5. Imagine writing your life story and summarizing a marriage in seven words. Brutal and brilliant.↩

6. The spiritualism thing is easier to understand if you think of it as both coping mechanism and weaponized empathy. If you spend enough time looking at misery, you have to believe something bigger is out there, or you’ll implode.↩

7. This wasn’t just rhetoric; it was a battle cry. The fact that it still resonates says as much about us as it does about her. We’re still drowning, just in different waters.↩

8. If this doesn’t immediately sound like a statement designed to make a 19th-century audience’s collective head explode, you’re either underestimating Victorian America or overestimating their tolerance for women saying anything, let alone this. It’s still terrifying to certain people today, which is probably why it remains so relevant.↩

9. Replace “railroads” with “Big Tech” and her warnings about democracy’s fragility feel unnervingly relevant. She wasn’t warning about trains; she was warning about systems—interlocking structures of power that grow more invisible the larger they become. ↩

10. Picture today’s most incendiary tweet multiplied by a hundred and dropped into a society that considered ankles scandalous. Obscenity charges would’ve seemed ridiculous if they weren’t so effective. Victorian morality wasn’t about decency; it was about control, a fact that should sound disturbingly familiar.↩

11. Her understanding of progress was as messy and chaotic as the world she lived in, which makes it all the more valuable. Progress isn’t a staircase; it’s a labyrinth, full of dead ends and false starts. The beauty of Woodhull’s vision isn’t that she thought the labyrinth could be solved but that she believed it was worth navigating, even when the walls seemed to close in.↩